Articles about Traditional Knowledge, Cultural Burns and Land Management

Traditional Aboriginal Burning in Modern Day Land Managemen

For over 50,000 years, Australia’s Indigenous community cared for country by using land management that worked with the environment. Using traditional burning, fishing traps, and sowing and storing plants, they were able to create a system that was sustainable and supplied them with the food they needed. When Europeans arrived, they brought farming practices suited to an environment very different to Australia, that in the long-term caused erosion and salinity.

While many historical European accounts of Indigenous land management have faded, today there is a shift to recognise that Indigenous people had sophisticated sustainable agricultural systems. There is growing adoption of these practices to repair the damage done by European farming. One example gaining traction is the use of traditional Aboriginal fire management.

Indigenous communities used fire across Australia, and in some areas this created expansive grassland on good soils that in turn encouraged kangaroos to come and were later hunted for food. Historians and researchers believe selecting what areas to burn, when, and how often, was part of Indigenous knowledge of the land. The result was a mosaic of trees and grasslands that meant the highly combustible Eucalyptus forests were not likely to create intense bushfires. With the arrival of Europeans, much of this practice has given way as fire became feared rather than harnessed as a tool to manage the scrub. The result was the grass plains gave way to thick scrub and bushland that was prone to intense bushfires.

Australian National University professor Bill Gammage, an expert of traditional Aboriginal burning, told Landcare in Focus the use of fire could be adopted across the country and used for a variety of land management problems. “Fire can be used for one of three outcomes. The first, to encourage native grasses to regenerate and produce new feed, the second to reduce scrub and fuel to prevent intense bushfires, and thirdly to promote biodiversity,” Bill said.

It is already in extensive use across the country, but particularly in the north where native grasses grow more vigorously in summer and need to be controlled, and where Indigenous communities actively manage the land. “On public land, national parks and public reserves and larger pastoral land it could be applied very effectively,” Bill explained. “Aboriginal people would apply it to very small areas, if necessary, like back burning along creek front or pushing back bush in grassland,” says Bill Gammage.

The adoption of traditional Aboriginal burning requires a sound understanding of local conditions to ensure it is effective and safe. “Local conditions, climate, plants, and animals, all matter and have to be taken into consideration,” Bill explained when considering the fire stick farming. He also said land managers need to understand how plants relate to fire and that this was local knowledge.

The type and timing of fire was dependent on the season and location. This was important, particularly in the north where grasses dry out and a fire would be uncontrollable. Bill said fire was used at a time following the wet season while the grasses and soil was still damp.

Across Australia there are a number of groups that work with farmers and Indigenous people and encourage them to work together to share knowledge and manage the land. Some of these groups include Local Land Management, the Aboriginal Land Management Councils, and Landcare groups.

These groups encourage farmers and Indigenous people to work together to adopt land management practices closer to those used by Australia’s first inhabitants. While the use of fire is not the only tool, it is one the Indigenous community can share.

By Christopher Gillies

On the Air: BBC to Feature Landcare Australia Film on Cultural Burning

The BBC is broadcasting audio and vision excerpts from a Landcare Australia film in three of its programs later this year. The focus is Traditional Owners and cultural burning practices in Australia.

The BBC productions include interviews with Victor Steffensen, a descendant of the Tagalaka people and Indigenous fire practitioner, explaining how cultural burns can help manage the land while reducing fuel load and destructive wildfires.

Audio from the film Fire and Water, Healing Country and People, produced for Landcare Australia’s 2021 National Conference, can now be heard on the BBC Radio Four program 39 Ways to Save the Planet. This podcast, delivered in partnership with the Royal Geographical Society, examines 39 ideas to relieve the stress that climate change is exerting on the planet. In his story on the importance of local wisdom, presenter Tom Heap considers if valuing and applying the knowledge of Indigenous people and groups more could help fight climate change. Listen to the podcast here.

The weekly BBC World Service solutions program People Fixing The World is doing its own take on Tom Heap’s report. They will also feature audio clips from the film of Victor Steffensen talking about his fire and land management techniques. People Fixing the World covers stories about people with innovative ideas to solve problems, and its content reaches a weekly audience of approximately 12 million. Listen to the podcast here.

Excerpts from Fire and Water, Healing Country and People will be included in a film that focuses on cultural burning practices in Australia. The film is part of a series of short films produced by BBC Studios for BBC Earth’s social media channels and will be published online in late 2021.

Filming of the cultural burn and interviews took place at Kanjuini at Emerald Creek, Queensland, near Cairns.

Landcare Australia produced the film Fire and Water, Healing Country and People for its 2021 National Landcare Conference. It was shown as part of a cultural land management panel that discussed integrating Indigenous perspectives for better land management. Facilitated by Doug Humann, AM Chair of Landcare Australia, the panel speakers included Victor Steffensen (Firesticks Alliance), Barry Hunter (Aboriginal Carbon Fund), Dhani Gilbert (2021 Young Landcare Leadership Award winner), and Joe Morrison (Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation).

This film is an important legacy from the 2021 National Landcare Conference. Following Victor and Barry allows us to see through the eyes of Indigenous land managers why actively managing Country is important for people and Country. The film reminds us all as Landcarers that there are many ways of looking at Country and that Country will be healthier if we work in partnership and trust together,” said Doug Humann AM.

You can watch Fire and Water, Healing Country and People on YouTube.

Workshops Share Traditional Knowledge of ‘Cultural Burns’ as Fire Management

Ancient traditions of land management by fire have been handed down to generations of Aboriginal people. But as with some Indigenous languages, there is a fear that knowledge will be lost.

Victor Steffensen wants to make sure that doesn’t happen. “I find myself following on from those old people who have passed and continuing the journey of educating and teaching the younger people just like I was taught,” said Mr Steffensen an Indigenous fire practitioner from Cape York. “My big dream is to see the culture of fire in Australia change, where everyone knows the country, knows fire properly and looks after the landscape again.”

Mr Steffensen works with a group called the Firesticks Alliance, an Indigenous organisation that runs programs with communities across Australia to build recognition of cultural fire management, and to reintroduce it onto lands owned and run by Aboriginal people.

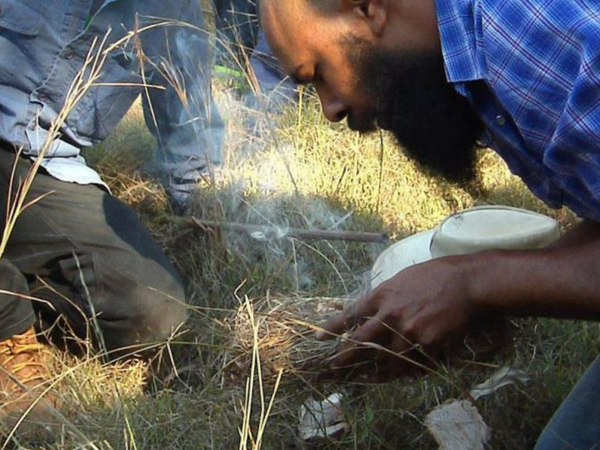

Now interest is growing among the wider community too and the practice has caught the attention of National Landcare Programs which has helped fund a joint workshop hosted by the Northern Tablelands Local Land Service (LLS) and the Banbai Aboriginal Corporation. Local landholders, fire agencies and Aboriginal Land Councils from around the North Coast and New England were invited to see how cultural burns are done. “The workshop is about understanding the benefits of what Aboriginal people are doing in respect to fire burning and why they do it, when they do it and how they do it,” land service officer Harry White said. “We then hope others can transfer these results into their property.”

The LLS has been working on its Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) with Indigenous rangers to carry out these types of burns for many years — and there is much more to it than simply lighting a match. “There has to be adequate training, referrals to ecologists, both flora and fauna, interaction with the Rural Fire Service and permits to make sure it’s done properly,” said Mr White. Fire is used to heal land that has often been overrun by weeds and non-native species, which over time has changed the animal species living there as well. The aim is to restore the country to its natural state. That will take generations — and workshops like this one are just the beginning.

“We’re working across Australia to reintroduce cultural fire regimes back into the landscape,” Director of the Firesticks Alliance Oliver Costello said. “It’s really important those agencies come on board to these indigenous-led processes.”

The Rural Fire Service was one of those agencies taking note. “We’re definitely here today to learn about traditional practices and we’re also here to see how we can assist them with getting the traditional landowners back on the country and doing what needs to be done in terms of their culture,” said Ivan Perkins, RFS community protection planner. Mr Perkins says the key is not just learning how it’s done but communicating with neighbours and other agencies as well when a fire is taking place.

“At the end of the day, by a cultural burn taking place, there is a hazard reduction outcome — albeit it’s being done for a different purpose — but we’re reducing the fuels and the grass is being reduced making the community safer,” Mr Perkins said.

While these cultural burns at the moment are largely taking place on IPAs, they have attracted the attention of non-Indigenous landholders as well. “Absolutely fascinated and I’ve just learned so much,” land holder Mr Graham Lightbody said.

Mr Lightbody owns country near Tabulam, where he has been trying to manage weeds and hazard reduction.

“The issue I would like to explore more is working across land tenure boundaries,” he said.

“It’s always a challenge to limit fire within your property.”

The LLS said that it will continue to support the training of Indigenous rangers to learn traditional fire management practices with a view to making them available to the non-Indigenous community as well.

“There’s huge interest in how Aboriginal people do fire burns and why — and getting our people to facilitate the burn would be the ideal situation,” said Mr White.

Originally published in ABC New England

By Jennifer Ingall

Fighting Fire with Fire

Covering over 20,000sq km, the Arnhem Land plateau is a rugged, ancient sandstone formation of sheer escarpments and gorges located 350km from Darwin in the Northern Territory.

The sandstone heathlands of the plateau are a significant ecological community of native shrubs, grasses and animals, many of which are threatened by destructive wildfires, disturbance by feral animals and invasion by weeds.

The Bininj Aboriginal people of West Arnhem Land have owned and cared for this country for more than 60,000 years. Today, Traditional Owners and Indigenous ranger groups are working in partnership with scientists, natural resource management organisations and government to help protect the plateau.

Territory Natural Resource Management is supporting a collaborative five year regional approach to protecting significant places and species in the West Arnhem and Kakadu region through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.

As part of the regional approach, Indigenous rangers, scientists and other experts gathered at a workshop hosted by TNRM, to plan activities to enhance management of the West Arnhem and Kakadu region.

A priority from the workshop was actioned in May, when TNRM, together with the Jawoyn Association and Kakadu National Park organised a fire management camp at Jeywunaye (Sleizbeck) on the upper Katherine River, surrounded by the rugged Arnhem Plateau.

The camp aimed to implement fine scale early dry season burning to help protect the fragile sandstone heathlands from hot extensive wildfires later in the season.

The camp was attended by 60 Traditional Owners and Indigenous rangers from Kakadu, Jawoyn and Mangarrayi. The rangers conducted fine scale ground burning and were dropping into sites in the rugged sandstone country by helicopter, to walk ground burning lines, offering the opportunity to share ideas about what good fire and healthy heath country looks like.

For more information visit: territorynrm.org.au

Traditional Owners Caring for Country

For the people of the Oak Valley community, the founding of the Oak Valley Rangers in October 2018 holds acute significance. Undertaking specific land management activities across the Maralinga Tjarutja Lands within the Alinytjara Wilurara region of South Australia, six permanent rangers – all members of the OV community – work closely with a casual staff of 12 Anangu people.

It’s a huge achievement for all the people of Oak Valley community and Maralinga Tjarutja who always had a vision of Traditional Owners employed to manage the land that has always belonged to them. ‘Indigenous Ranger and Protected Area programs are proven success stories, not only for the health of our natural heritage but for the lives of Indigenous people,’ said Sharon Yendall, General Manager of Maralinga Tjarutja Lands, Oak Valley Community. ‘To be an OV Ranger means that the outside world has recognised that caring for country and maintaining culture is important enough to create jobs to do so. Within OV, a Ranger job is a real job, which means that there is a pathway from dependence and a chance to fulfil long-overdue responsibilities to country.’

In the past 10 months since starting on-ground works, the OV Rangers have undertaken, through a mixture of overnight and day trips, multiple surveys to assess the overall health of the country with a focus on the presence of threatened and introduced species.

The Nganamara (Malleefowl) Leipoa ocellata is threatened in the region by introduced carnivorous predators: feral cats and foxes. With their extensive knowledge of country the OV Rangers monitor, check known nests and survey new areas to determine and record the impact of these species on the Nganamara population.

Elsewhere, significant on-ground land management outcomes were achieved including 1,200-2,000 hectares burnt in accordance to traditional land management practices.

The OV Rangers have worked with many different organisations and individuals, including the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, NRAW, the 10 Deserts Project and the Indigenous Desert Alliance (IDA). Not to mention the support and work of the Traditional Owners and field ecologists to identify priority works for the MT Lands.

OV Rangers won the Indigenous Land Management award at the 2019 SA Landcare Awards.