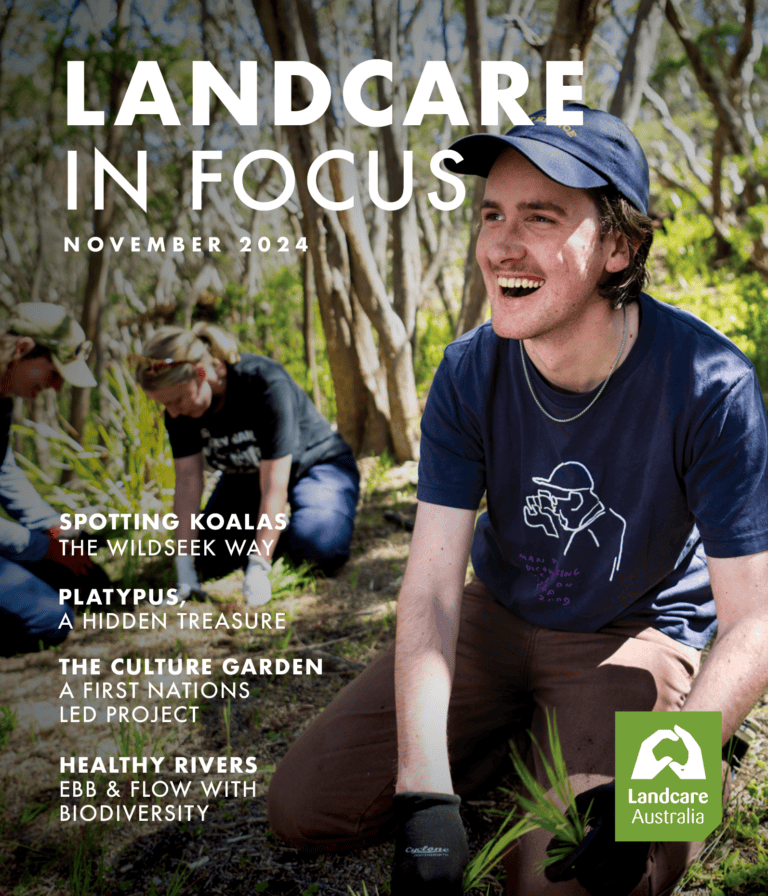

Get In Focus with Landcare

Landcare In Focus is a biannual online magazine that features case studies, project information, photos, people profiles and science-based articles submitted by volunteers, groups and organisations involved in landcare from across Australia.

The magazine content showcases articles about innovation in sustainable land management, revegetation and habitat restoration, protection of waterways, community participation in landcare projects, and excellence in agriculture and environmental stewardship. The magazine profiles the people across Australia who are actively caring for our natural environment.

Latest Magazine - May 2025

Content Submissions

The editorial team actively encourages content submissions, including photography. For more information about the content submission and editorial guidelines please read our guidelines.

The publishing schedule and content deadlines for 2025:

May 2025 – content deadline March 31, 2025.

Nov 2025 – content deadline September 1, 2025.

Content submissions or enquiries should be sent to The Editor at [email protected]

Counters

Lorem Ipsumbdgdh

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.nfghf

Lorem Ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Lorem Ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.