Climate change stalls Australian wheat yields

By Zvi Hochman, CSIRO

A CSIRO study published in Global Change Biology has found that declining rainfall and rising maximum temperatures are impacting the yield potential of Australia’s $5 billion wheat industry.

The study of 26 years of data from 1990 to 2015, gathered from 50 weather stations across Australia’s wheat-growing zone, demonstrated an average decline of in-season rainfall of 28 per cent, and an increase in average maximum temperatures of 1℃ over this period.

CSIRO Senior Principal Research Scientist Dr Zvi Hochman said the adverse conditions have resulted in an average decline in yield potential of 27 per cent, from 4.4 tonnes per hectare to 3.2 tonnes per hectare.

The findings of the study represent an Australia-wide average across the 50 sites, where some sites have been more

dramatically affected than others.

“There have been good years and lean years, but the fact is that the average harvested wheat yield Australia-wide has been stagnant since 1990, at an average of around 1.74 tonnes per hectare,” Dr Hochman said.

“It is important to stress that these findings are not forward projections – these are observed instances of how climate change has already impacted agriculture, and the probability of these observations occurring by random climate variability is less than one in 100 billion.”

Advances in farming technologies and practices have helped to offset the decline in yield potential, resulting in the average farmer becoming more efficient. Nationally, farmers have closed the gap between potential and actual yield from 39 per cent in 1990 to 55 per cent in 2015.

“To date, farmers have done well to keep pace with climate change and not reduce their actual yields, but in effect the national average yields have seen them standing still despite all of their hard work.”

Dr Hochman said that while there is further room for the average farmer to close the yield gap, there are economic limits that effectively prevent farmers from consistently reaching a crop’s full yield potential.

“Once farmers achieve approximately 80 per cent of their yield potential, it becomes economically unviable to pursue further yield gains, with costs outweighing benefits,” he said.

When asked to comment on the future implications for wheat growers, Dr Hochman said that farmers will need to continue to innovate and will have to be responsive to seasonal conditions to secure their futures.

“Advances in wheat varieties, and adoption of improved land and farm management practices will work in farmers’ favour. However, rainfall and temperatures will continue to be the most important determinants of yield potential,” he said.

“Worryingly, if the climate trend continues to negatively impact rainfall and temperatures at the rate observed in the previous 26 years, despite further advances it’s unfortunately likely that average yields will begin to fall by the 2040s.”

While the study’s focus was on wheat production, Dr Hochman said the findings could be broadly applied to other cereal grains, pulses and oilseed crops, which are largely grown in the same regions and during same season as wheat.

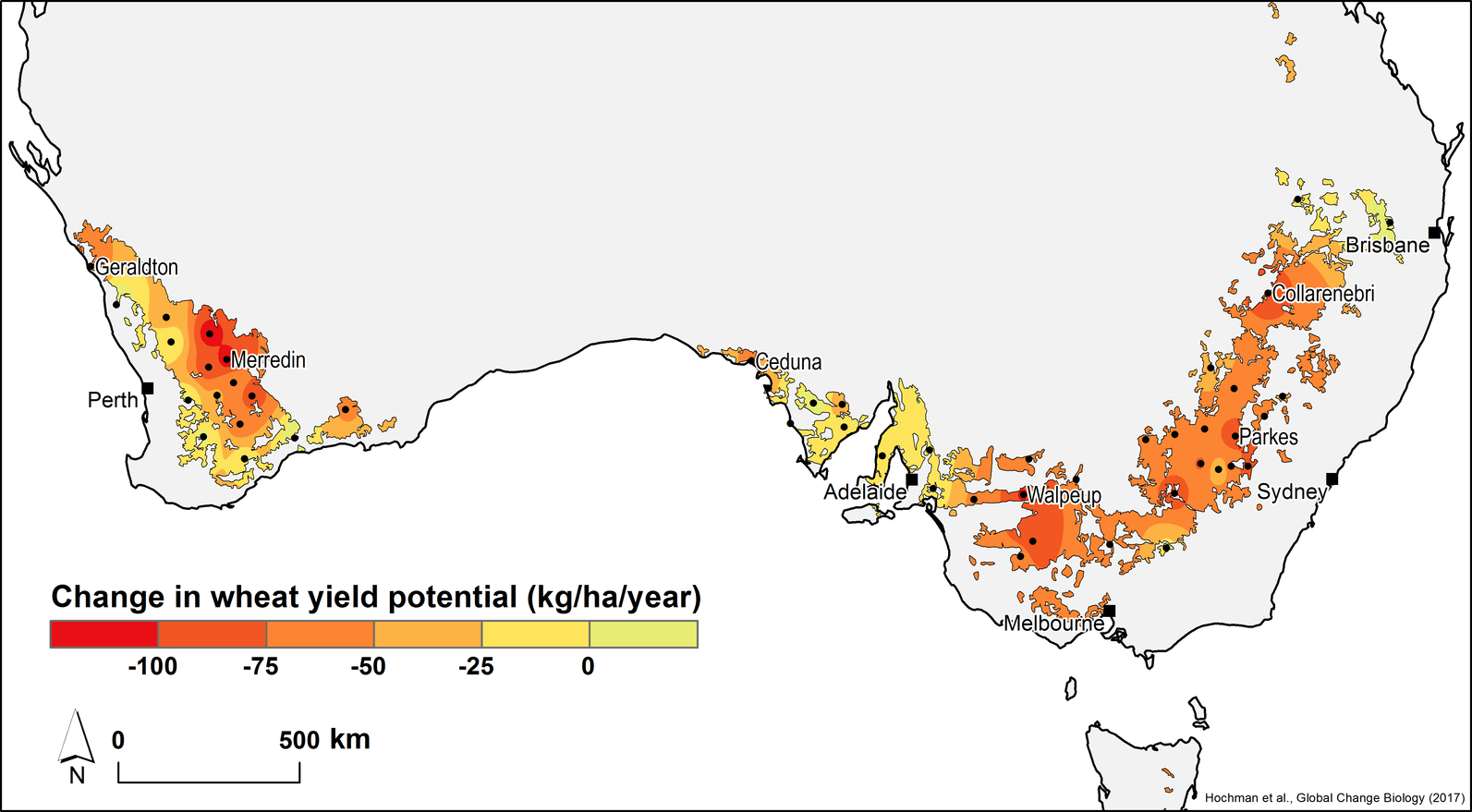

The findings of the study represent an Australia-wide average across the 50 sites, where some sites have been more dramatically affected than others (see map).

“The future of marginal growers in the more severely impacted areas may lie beyond wheat or their current crops. One possible adaptation could be an increase in mixed enterprise farming to help with cash flow during the lean years.”

For more information, contact [email protected].